The House of Krug

Krug, the most venerable of all champagne houses, was founded by Johann-Joseph Krug in 1843. Previously he had worked for Jacquesson but he had itchy feet and, despite the fact that he was married into the family, he struck out on his own in 1842 and moved to Reims where he set up in business the following year. Today, the firm that still bears his name is now under the stewardship of sixth generation Olivier Krug, though ownership of the ‘family’ firm now resides with the international luxury goods group LVMH, who bought Krug from Remy Cointreau for the headline-making figure of one billion French francs in 1999. Billions may be as common as muck these days, lost billions that is, but that was a whopping figure, even when translated into a more meaningful one hundred and ten million pounds sterling. It only made sense when the value of the brand and the millions of bottles of ageing stock, amounting to about six years’ worth of sales, were factored in.

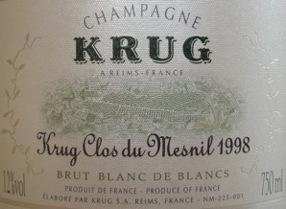

Left: Olivier Krug conducting a tasting in Reims and, right, one of Krug’s most desired wines.

Krug as we know it today could be said to date from the period before the LVMH takeover, from the decade that gave us little else by way of good taste: the 1970s. As we clumped around in ludicrous platform shoes, wearing jackets with lapels so wide they could have doubled as hang gliders, the people at Krug were laying the foundations for future success. They started the decade by purchasing the Clos du Mesnil vineyard and ended it with the launch of Grand Cuvée, which replaced Private Cuvée as the firm’s flagship wine.

Clos du Mesnil is now almost unique amongst champagnes, being a cru or single vineyard wine, where practically every other one is blended from many sites across the region. The vineyard covers about two hectares and was completely re-planted with Chardonnay vines that yielded their first vintage in 1979. Since then its reputation has soared, built on a flavour that is rich and concentrated, serious and intense, elegant and complete. More memorably for followers of the marque, 1979 saw the introduction of the oh-so-elegant, swan-necked bottle that replaced the standard champagne bottle which had been used up to that. Judging a book by its cover may be a dubious practice but in this case the bottle shape, as much as its contents, helped to set Krug apart. Without being in any way brash it managed to be as instantly recognisable as its contents were memorable. The bottle was used to launch the new wine, Grand Cuvée, whose character was harmonious and balanced with great depth of flavour.

And no wonder. ‘Painstaking’ barely describes the blending process, which can see anything up to 100 wines from between seven and 10 different vintages, some aged up to 15 years, blended together and then cellared for half-a-dozen years before release. Krug insist that the best wines are used for Grand Cuvée before the other wines in the range, such as the vintage (if declared) and the rosé, are made. The latter, the most sensual of all the Krug champagnes, is a hedonist’s treat. Should fortune ever smile on you in the form of a bottle of this then proceed with great caution when planning its consumption. It should not be served to a crowd, nor should it be wasted amidst the raucous joy of a ‘special’ occasion. A deux is the way to enjoy it, perhaps accompanied by some perfectly cooked baby lamb cutlets without any palate-pounding herb crusts and the like. That way the gorgeous red fruit flavours will shine while the fuller, savoury notes will link up perfectly with the meat.

The rosé represents only a small fraction of Krug’s total production which itself, at about 600,000 bottles per annum, only equates to 0.2% of the entire production of champagne. It is all at the luxury end of the market, however, where there is now huge competition as the houses vie with one another to launch ever more exclusive and elaborately packaged prestige cuvées. There is no room for those who are keen to rest on their laurels. Krug entered the fray big time in 2007 when Clos d’Ambonnay, made exclusively from Pinot Noir, was launched. In many respects it is the Pinot equivalent of Clos du Mesnil’s Chardonnay except that the Ambonnay vineyard is only about one-third the size of Mesnil. Thus it was launched at a sky-high price and now trades at prices well north of €2,000 per bottle. If our Celtic Tiger was still roaring it would no doubt be the property developers’ favourite tipple.

Notwithstanding such distractions Grand Cuvée remains the Krug flagship and recent years have heard some mutterings amongst the critics that it is not what it once was, that some of the signature ‘weight’ of the style has been sacrificed in favour of a more approachable, ‘user-friendly’ flavour. It is a contention that Olivier Krug flatly rejects though he is prepared to concede that production has increased recently. He is just the man to address such criticisms, for he is a voluble and articulate ambassador for the firm, tirelessly carrying the message to all corners of the globe, in the process almost single-handedly creating the Japanese market for Krug. Yet it should not be forgotten that LVMH, who allow their champagne houses such as Veuve Clicquot, Ruinart and Moët et Chandon considerable autonomy in the running of their affairs, have the ultimate say in the future direction of the House of Krug.

Article originally published in Food & Wine Magazine, December 2010